Exploring Archigram: A Revolutionary Movement that Redefined Architecture

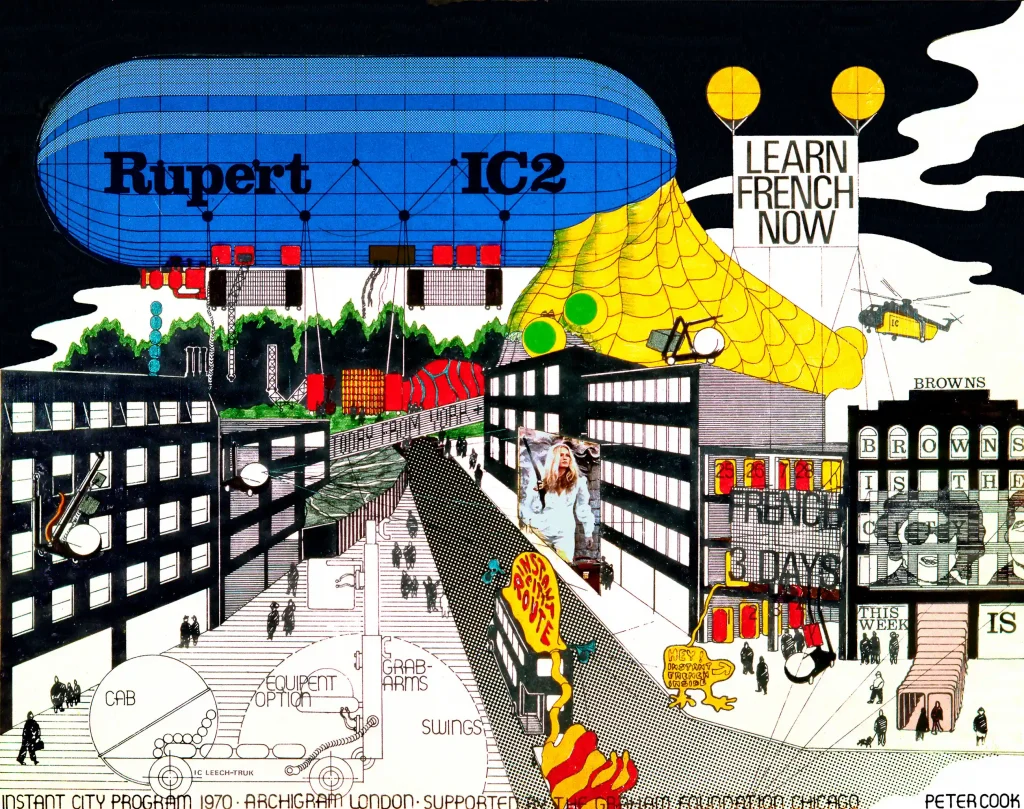

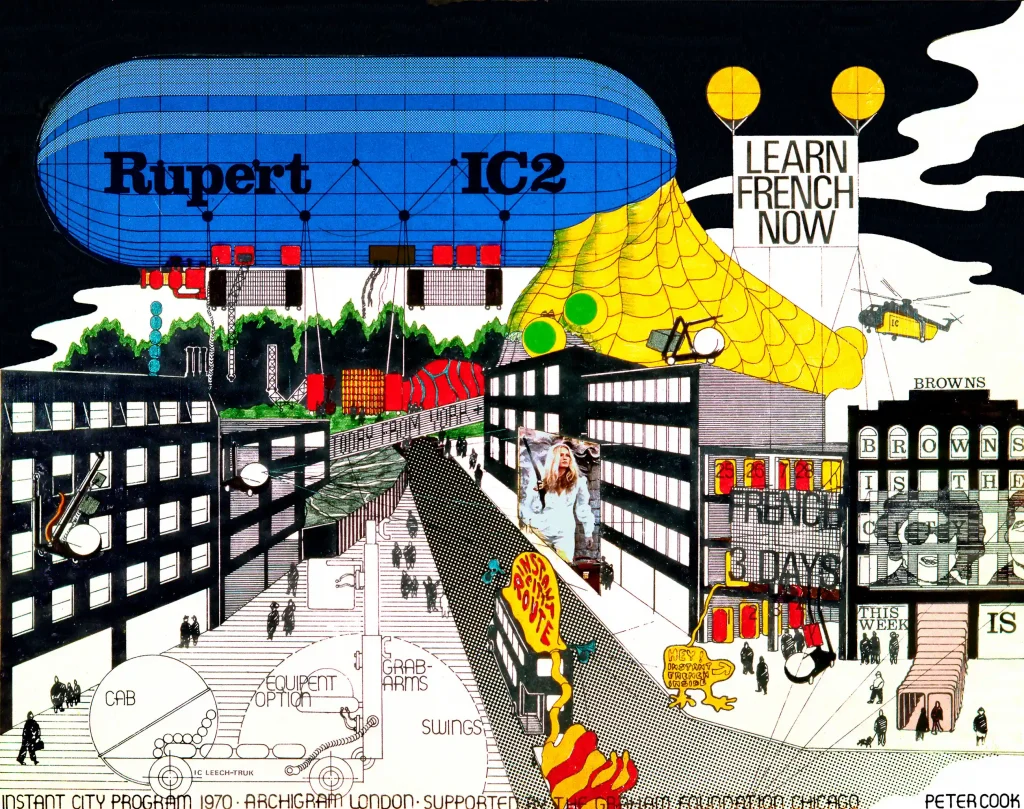

Have you ever come across the cover image of this blog before? What do the use of colors in these images and the drawing techniques of the depicted spaces tell you? Do you think these drawings are depictions of a utopian or dystopian world?

These fascinating visuals first emerged from the idea of forming a fanzine together by a group of architect friends sitting in a cafe in 1961. Who knew that this fanzine would grow and become a significant trend released between 1961 and 1974 and added to the architectural archives?

Founded by Peter Cook, David Greene, and Mike Webb, Archigram took inspiration from pop culture and comics to produce a series of visual publications that called for a change in the world of architecture. Their manifesto, “Eight Alternatives for the Future,” was presented by Peter Cook in 1960 at the London Environmental Architecture Conference. Cook imagined a future where architecture is faster, personalized, detachable, more precise, convenient, and expendable. The group believed that old dogmas would become invalid, and a new language and thought fueled by space capsules, calculators, and electro-automatic devices would replace them. Therefore, they developed a brand-new visualization technique to demonstrate their thoughts and created this intriguing piece of art.

This group of architect friends envisioned a brand-new future where the movement would start from the building scale and spread to the environment. They wanted to create a new agenda where nomadism, which we explored in a previous blog post titled “Unpacking Neonomadism: The Ultimate Guide to Full-Time Mobile Living,” was the dominant social force, stagnation was replaced by change, consumption was encouraged, and emphasis was on temporality. They believed in technology and consumption in the utopias they produced and associated mobility with freedom.

Archigram is one of the most important influences that an architect or designer could benefit from. Their unique perspective and visualization techniques have inspired much architectural literature. After understanding their motivations and purposes, we can now focus on the projects. As Serai’s design team, we are aware that by understanding their motivations, techniques, and projects, architects and designers today can continue to be inspired by their visionary work and push the boundaries of what is possible in design. So, let’s take a closer look at this unique movement together.

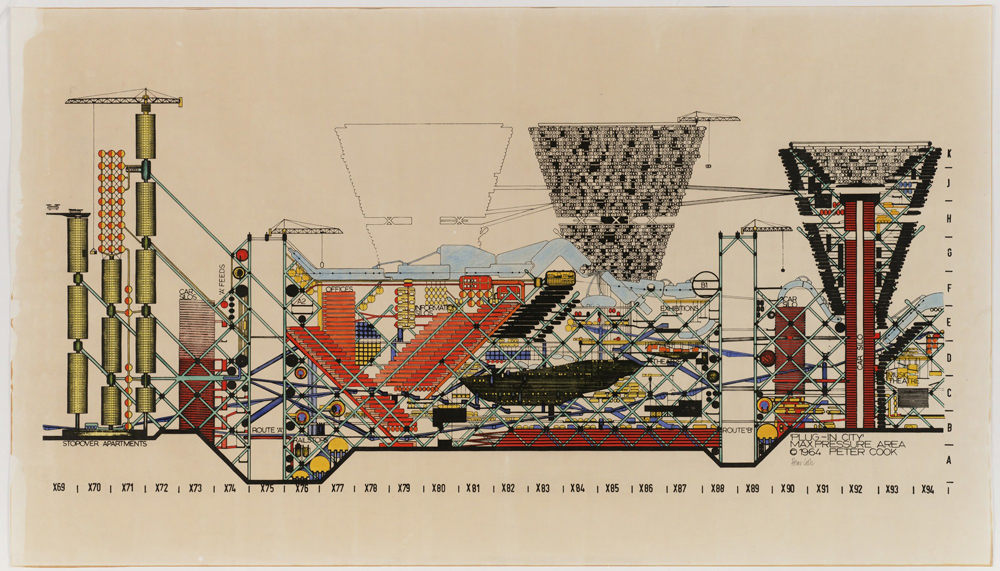

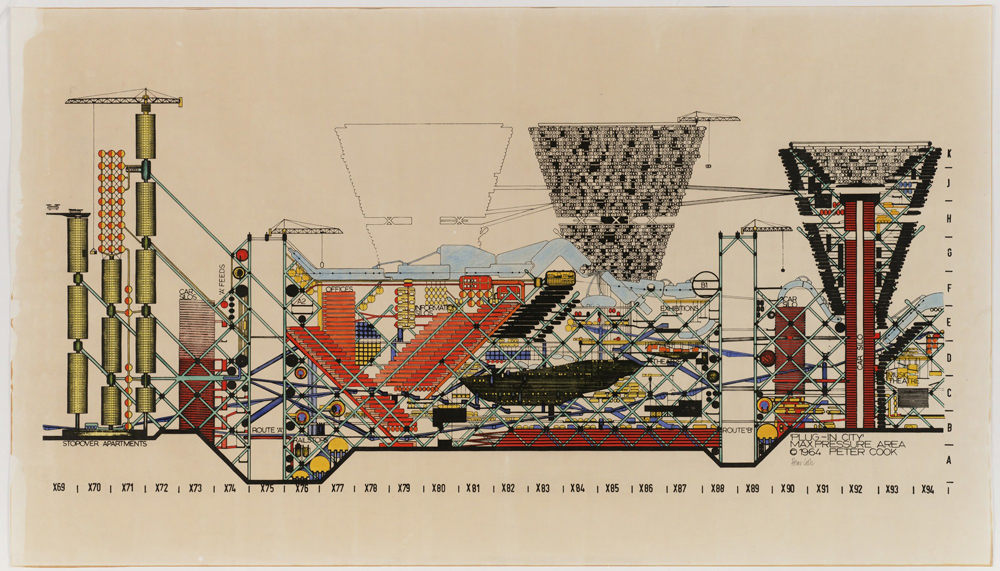

Their first project, the Cabin House Project, was created with the plug-in concept. This idea was further developed and reached its peak with the Plug-in City project, which investigated what could happen in the future by programming and structuring the entire urban environment for change. The giant space frame that can expand across national borders and beyond offers a flexible and expendable way of life.

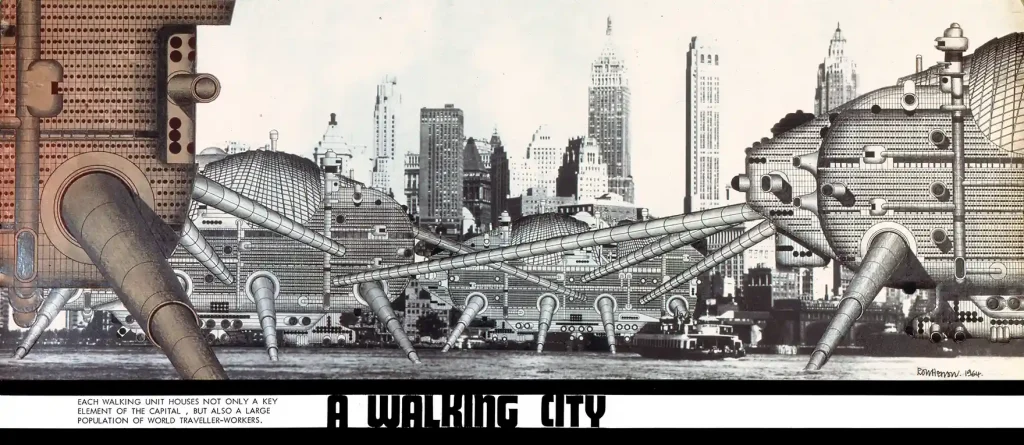

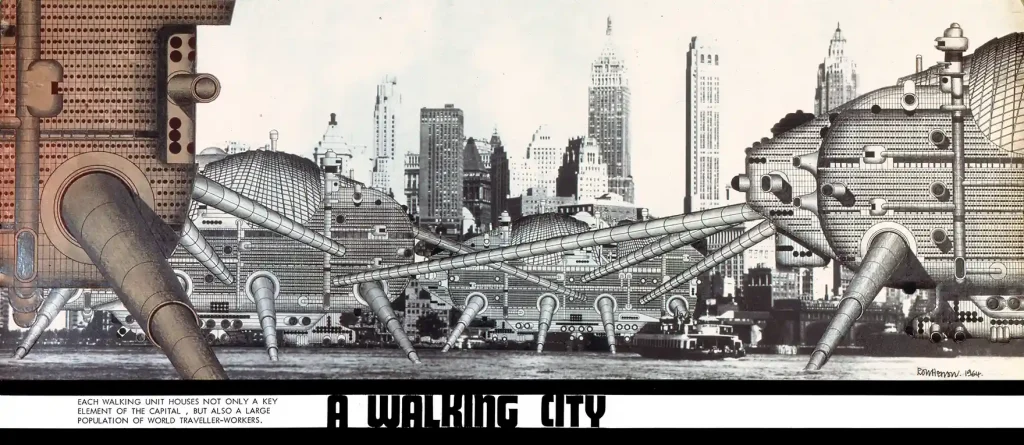

The Walking City is constituted by intelligent buildings or robots in the form of giant, self-contained living pods designed to roam freely. The form derived from a combination of insect and machine and was a literal interpretation of Le Corbusier’s aphorism that a house was a “machine for living in.” The pods were intended to be independent yet parasitic since they could “plug into” way stations to exchange occupants or replenish resources. The imagined context for these ambulatory, high-tech structures was a post-apocalyptic future in which the urban landscape lay in ruins, devastated by a human-made catastrophe.

Although Archigram’s projects were generally on a city scale, they also worked on houses, exploring the possibilities of small-scale mechanical structures that respond to personal needs. The group sought to answer the question: Plug-in City is fine, but how do we put these ideas on a smaller scale?

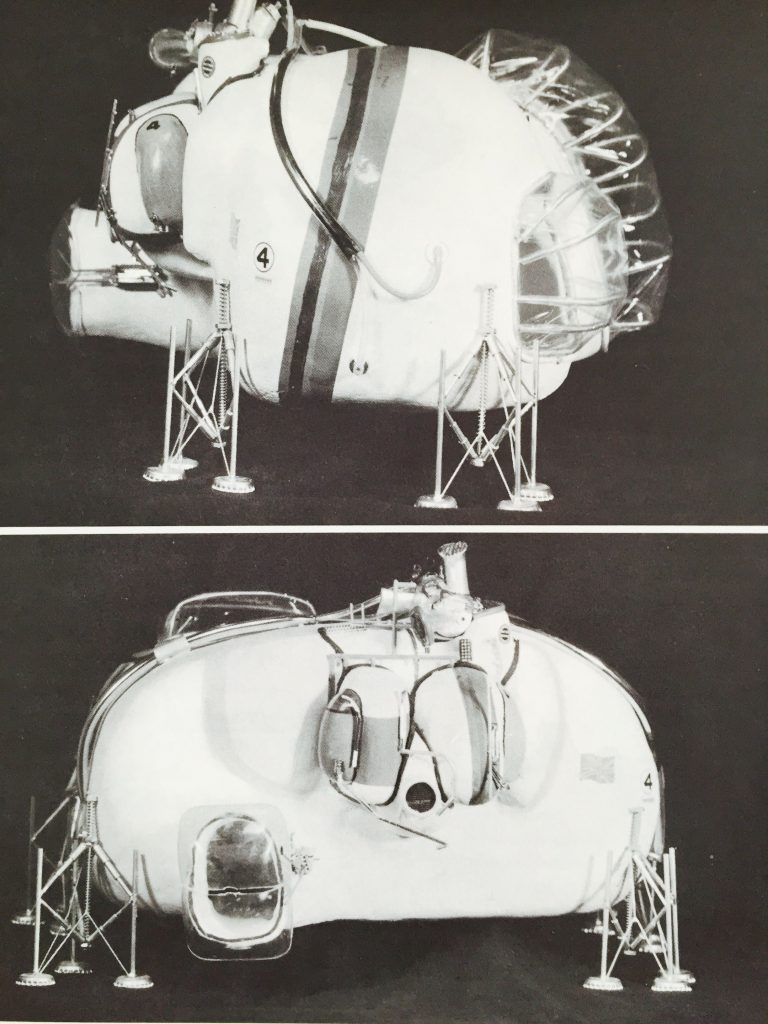

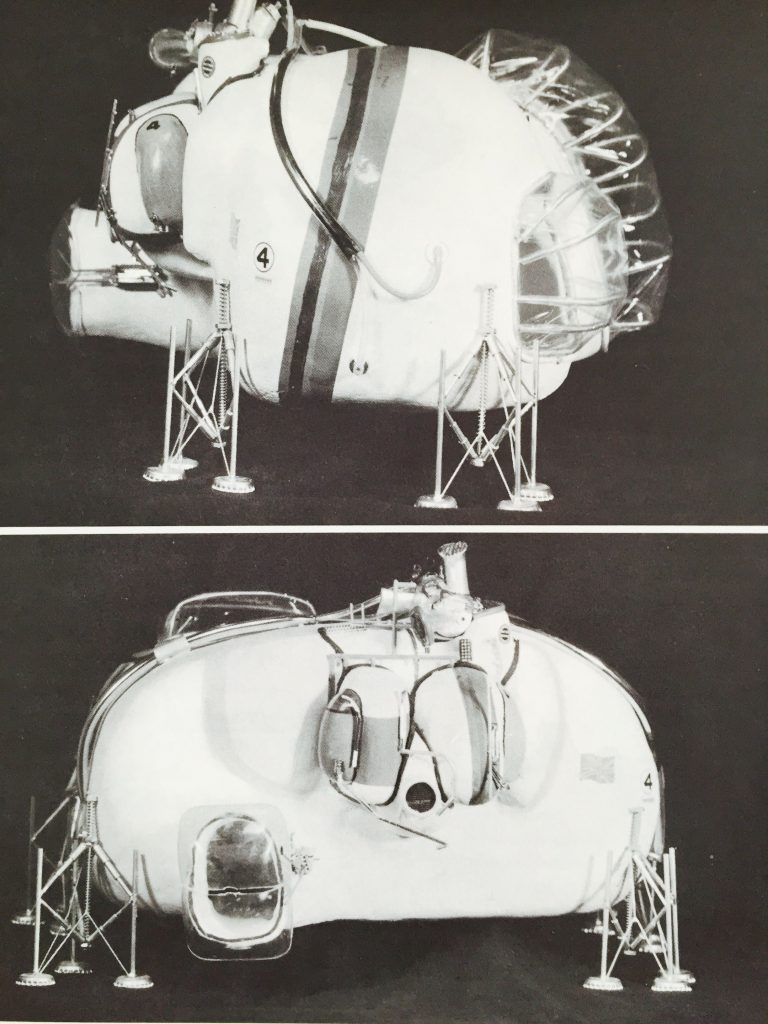

Living Pod, designed by Archigram member David Greene in 1965, stepped out of the mega structural scale. Temporary, flexible, and mobility themes are at the center of the story of “disappearing architecture.” The project is like Le Corbusier’s approach to housing with its flexible, technological, and engineering features. Le Corbusier’s analogy of the house to a machine caused Archigram to take a proactive stance in this regard. David Greene argued that a home is a tool we carry with us, and cities are a machine to plug in. With this aspect, Living Pod’s lifestyle to its users is very close to the life of today’s digital nomads. They can also use any area as a home where they can physically feed the electronic devices, they carry with them. In addition, the Living Pod can be attached to mega structures in the urban area, or it can be a single-use house in the field. In a scenario where individual mobility comes to the fore, the mobile home is imagined as a land trailer. In this respect, it has highlighted the sense of curiosity and research by destroying the perceptions of continuity and security.

The ideas of a future city belonging to the group were fast, mobile, and constantly changing, with an emphasis on consumption, they have inspired many architects and designers until today. They believed that the possibilities for technology and design were endless, and they pushed the boundaries of what was possible. Today, Archigram is remembered as a visionary group that imagined a future beyond the limits of the present. Their work continues to inspire architects and designers to think outside the box and embrace the limitless possibilities of technology and design. This group of architects’ legacy, still living for those who dared to imagine a radically different future for architecture and urbanism. Their pioneering spirit and willingness to experiment with new forms, technologies, and ideas have left a lasting impact on the field.

References

- Uğur Tanyeli, Garanti Gallery Archigram Exhibition Brochure Text, (2005).

- Ege Ceylan Baba, Architectural utopias in search of the ideal city, YEM, İstanbul, (2020).

- Akın Sevinç, Utopia: Imaginary people’s project, Okuyan Us, İstanbul,(2004).

- Sedat Gürel, New Developments in Space Organizations, ITU Faculty of Architecture, İstanbul, (1968).

- Robert Kronenburg, Houses in Motion: The Genesis, History and Development of the Portable Building, Chichester: Wiley Academy, (2002).

- Dennis Crompton, Concerning Archigram: Published on the Occasion of the Exhibition Archigram: Experimental Architecture 1961-74 at Cornerhouse Gallery, Manchester London: Archigram Archives, 1-4 (1998).

- Warren Chalk, “Things that do their own thing”, Architectural Design, 39/7 (1969): 376

- Dennis Crompton, Concerning Archigram: Published on the Occasion of the Exhibition Archigram: Experimental Architecture 1961-74 at Cornerhouse Gallery, Manchester London: Archigram Archives, 1-4 (1998).

- David Greene, Living Pod, Architectural Design, London, (1966).

If you are interested in experiencing this innovative way of life, please have a look at our other blogs.

Discover the Serai Way of Life: Living Environment for Everyday Details

The Art of Minimalist Living: Exploring the Rising Trend of Minimalist Spaces in the 21st Century

Serai Design Office: Building Architectural Sections with a Focus on Serai One – A Zoomed-In Look

Also, don’t forget to visit our website!

www.seraispaces.com